Photopoetry

More than ten years ago in a special issue of the British photography magazine Source that was dedicated to the relationship between photography & literature, I wrote this: “If one were to look for the most innovative and challenging uses of photography in literature today, I would point to a handful of contemporary poets who are finding ways to turn visual images into poetic vocabulary.” Today, I would go even further and say that, except for a handful of novelists, that statement is true for the last century or so. When it comes to creating a work of literature in which the writing and the photographs are co-dependent, causing the reader to use both aspects to “read” the work stereophonically, shall we say, in order to create a richer work, poetry has seemed the better avenue than fiction. Just take a look at any of Don Mee Choi‘s three extraordinary multilingual, photo- and image-infused books of poetry or one of Leslie Scalapino‘s very different approaches to mixing poetry with photographs or many more titles that you can find in the ongoing Bibliography I am compiling that you can find at the top of Vertigo.

I began this blog in 2007 thinking only about fiction and photographs—more specifically, about the four books of prose fiction by W.G. Sebald and the strange, sometimes puzzling way in which he used photographs in them. As a result, I almost immediately settled on the phrase embedded photographs for those photographic images that I found within works of fiction. But seven years on, in 2014, I admitted some discomfort with that term, and I wrote that it “feels so inappropriately hierarchical, implying a subservient role to images.” But, after looking around for an alternative, I decided to “hobble along” with the term embedded photographs. Ten years later I am still using it. But Michael Nott’s book Photopoetry, 1845-2015: A Critical History (Bloomsbury, 2018) might get me to change my ways—at least with regard to poetry. Surprisingly, I have never used the word photopoetry in seventeen years of writing on Vertigo, but it’s certainly apt.

I’m not sure why I have not run into Nott’s book in the last six years (perhaps because I have never done a search using the word photopoetry?). By the same token, it seems pretty clear that Nott was not aware of my now massive online bibliography of fiction and poetry with embedded photographs, which I began in 2010 (perhaps because he never conducted a search using the term embedded photographs?) Nevertheless, I’m thrilled to have found Nott’s thoughtful, well-researched book and I highly recommend it for anyone interested in poetry or in photopoetry. After a short introduction, Nott divides his history into five distinct chronological sections, and then concludes with a short look at “Photopoetry and the Future.” In each of his chronological sections, he writes at some length about several representative books, while usually referencing a handful of others.

Nott begins by pondering the problem of defining photopoetry. After examining several existing definitions that other writers have come up with, he wisely writes “That poem and photograph interact is my sole demand.” Now that’s a definition of photopoetry that I like. Aware that he is writing “the first critical account” of photopoetry, Nott then situates himself with the work of other scholars and disciplines, placing his book within the current scholarly context. Then he begins with a study of “The Birth of British Photopoetry, 1845-1875.” These early books are ones in which the selection and layout of poems and photographs was almost exclusively done by editors or publishers, rarely by photographers or poets. These books don’t interest me very much because I am primarily concerned with titles in which either the author or the photographer is responsible for all of the content of the text— or in books in which both share the responsibility through collaboration. One of the crucial things that Nott notices about British photopoetry of this period is the focus on landscape and on place.

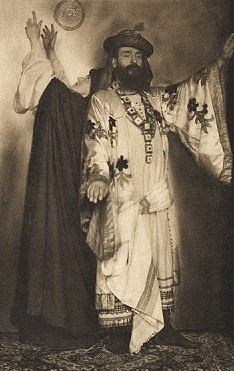

In his second section, “‘Illustratable with the Camera’: The United States and Beyond, 1875-1915,” Nott sees that “the American focus on people rather than place” tended to lead photopoetry into “engagements with identity-shaping ideologies—positive and negative.” As examples, he examines the issues of gender, slavery, and nostalgia that arise in the dialect poetry books of African American poet Paul Lawrence Dunbar, which were illustrated with photographs by the largely white members of the Hampton Institute Camera Club, and he discusses excursions into Orientalism via two versions of The Rubiyát of Omar Kháyyám, illustrated with Pictorialist-era photographs first by Adelaide Hanscom Leesom (1905), then by Mabel Eardley-Wilmot (1912).

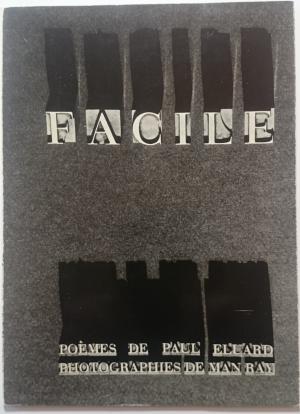

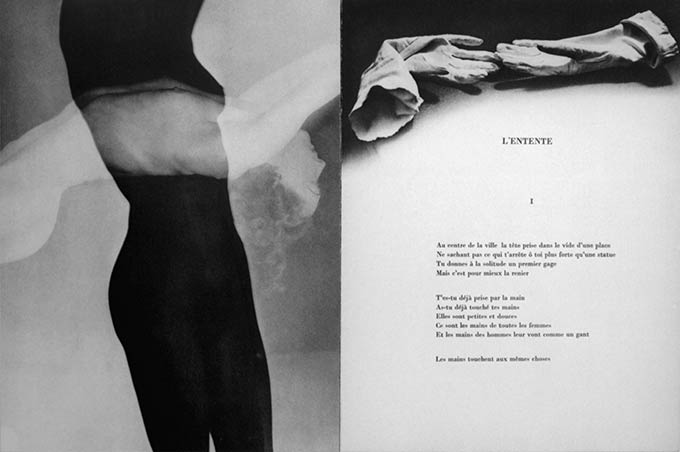

When Nott shifts to the twentieth century in “From Illustration to Collaboration: Picturing the City, 1913-1956,” he immediately turns to Ezra Pound and his Imagist poetics to help explain the dramatic shift that occurs in Modernist photography. Modernist poetry, with its frequent absence of pronouns, often gives the reader the sense that there is no middleman, that the reader is directly observing whatever the poet has observed. The Modernist photographer, by insisting that the camera is an objective machine, does much the same. There seems to be less “interpretation” going on in a Modernist photograph than in a Pictorialist one. Nott quotes the French literary scholar Nicole Boulestreau, who apparently created the word photopoème. She has suggested that a successful photopoem becomes “a self-creation by the reader.” Nott points us to what he calls an “iconic modernist work” in Paul Eluard and Man Ray’s Facile (1935).

In Nott’s fourth chapter, “Shaping Poetic Space, 1957-1994,” he really drives home his belief that the best photopoetic works are those that are collaborative ones between poets and photographers. The books that Nott chose to focus on for this period all have to do with explorations of the “connection between person and place [as] poets and photographers traversed the globe and came to live in, and engage with, specific locales, combining and juxtaposing their experiences in collaborative photobooks.” Some of the titles that Nott discusses in this section include Positives (1966) by Thom Gunn and Ander Gunn, Ankor Wat (1968) by Allen Ginsberg and Alexandra Lawrence, Remains of Elmet (1979) by Ted Hughes and Fay Godwin, and Orkney Pictures & Poems (1996) George Mackay Brown and Gunnie Moberg.

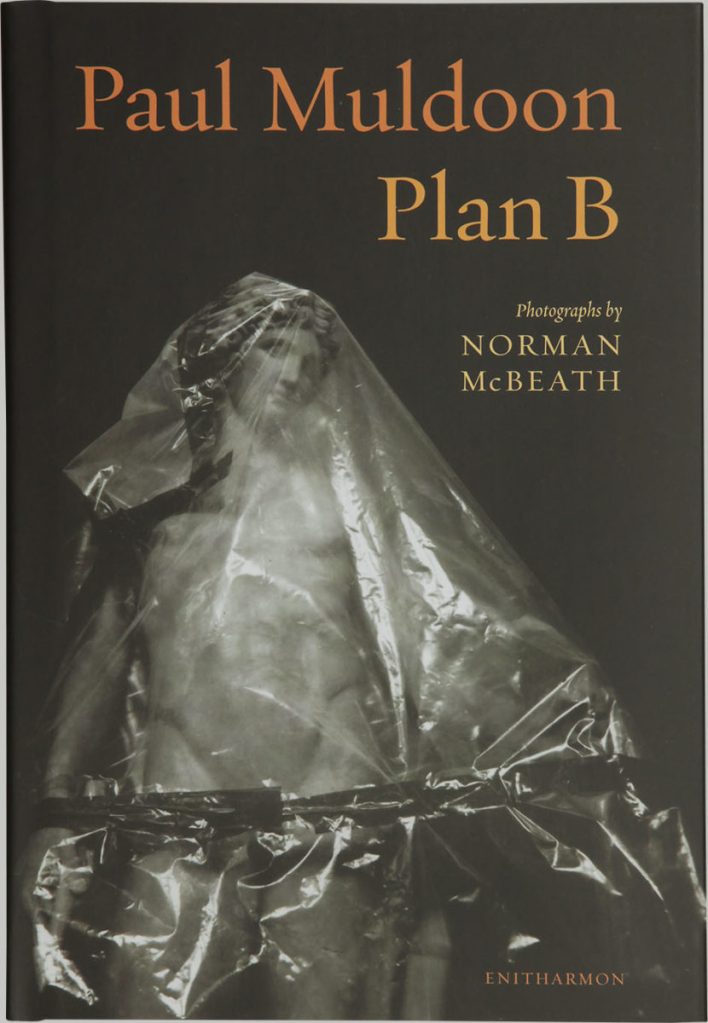

Nott’s final chronological period is called “Site Rhyme, 1992-2015: Photopoetry and the Architectures of Memory.” Nott suggests that the immersive combination of the visual and verbal photopoem “constructs an architectural space in our minds.” By the end of the twentieth century, “the poet and the photographer no longer lead the reader along a predetermined course.” Instead, readers often find that a book of photopoetry requires them “to muddle through unaided and find their own paths.” As examples, Nott gives close readings of four books: The Autonomous Region: Poems and Photographs from Tibet (1993) by Kathleen Jamie and Sean Mayne Smith and Sweeney’s Flight (1992) by Seamus Heaney and Rachel Giese, followed by two books of poetry by Paul Muldoon—Kerry Slides (1996) with photographer Bill Doyle and Plan B (2009) with photographer Norman McBeath. Nott acknowledges that it is very hard to generalize about photopoetry during this period and that each of these four titles represents a different aspect of the artform.

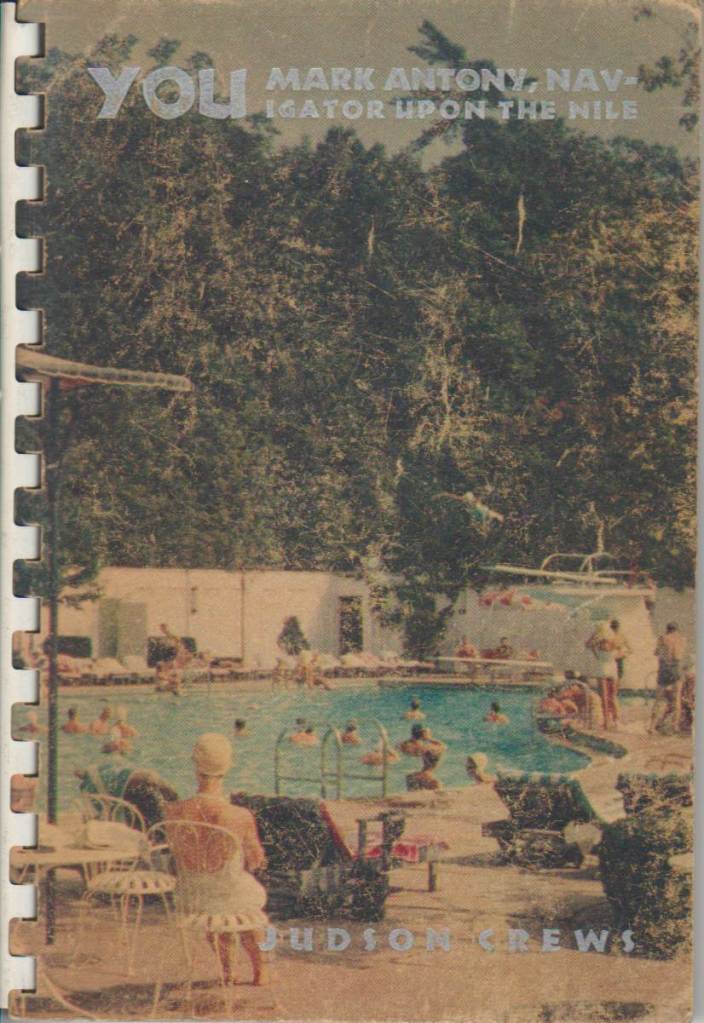

In his brief conclusion “Photopoetry and the Future,” Nott asks many questions about the future of photopoetry and makes a few suggestions about the directions it might take. Nott admits that his “interest lies primarily in the poetic half of the photopoetic collaborations,” and that is undoubtedly why he and I diverge on a couple of issues, since I primarily come from the photographic history side of the equation. In thinking about the role that digital photography might play in photopoetry, Nott quotes Fred Ritchin, a writer and photography curator, who, in 2009, posed the question: “Does the photograph still require a photographer, or even a camera?” Ritchin’s belated question was answered definitively four decades earlier in the mid-1960s when photographers like Robert Heinecken started taking photographs torn from magazines or found in antique stores or in family scrapbooks and used them in their art photography. As early as 1963 Judson Crews began making books of photopoetry using images from nudist and travel magazines, intermingled with his own poetry.

In a previous chapter, Nott had made the statement that “self-collaborative photopoetry” (his term for works in which a single person is responsible for both the poetry and the photography) “is uncommon.” “Given the problematic nature of self-collaboration, and its relative scarcity,” he decided to completely omit any discussion of such books, and he names two books that “would otherwise warrant inclusion in an encyclopedic history of photopoetry:” Anne Brigman’s Songs of a Pagan (1949) and Janet Sternburg’s Optic Nerve (2005). But if one defines photography to include snapshots, media images, archival photographs, and photography from literally any source, then self-collaborative photopoetry is not so uncommon. There are actually a number of books of photopoetry created by poets without photographers before 2015—and even more after that year. A few examples include Leslie Scalapino’s Crowd and not evening or light: a poem (1992), Anne Carson’s Nox (2010), Jeff Griffin’s Lost and, Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric (2014).

Nott, who is also an editor of The Letters of Thom Gunn (Faber) and a well-received biography of Gunn that has just been published, has made an exceptional contribution to a scholarly discipline that barely seems to exist even though photopoetry has been active for nearly 180 years. I feel bad about the impossible task of reducing his 291-page book to this single blog post, and so I urge you to read this affordable book for yourself.

A very helpful review that prompts the purchase of some new books, Michael Nott’s book Photopoetry, 1845-2015: A Critical History to start with!

High praise from me for this wonderful resource accrued over the many years of your blog.

I am interested to discover what you might think of ‘literature embedded photography’ like Ed van der Elsken’s Een Liefdesgeschiedenis in Saint-Germain-Des-Prés and the special category of children’s books illustrated with photography like Riwkin-Brick’s first photo book for children Elle Kari 1951, the first Swedish picturebook with photos to follow the everyday life of a child in a continuous story.

James

James, Thanks for the comment and the kind words. I hadn’t thought of Ed van der Elsken’s Love on the Left Bank in decades. I’ve never owned a copy and I don’t remember when or where I saw one, but I was immediately charmed and in love with Paris and his photography. I see now that it is quasi-fictionalized and so it does belong in the bibliography. (A number of other titles are similarly barely fictionalized stories.) I don’t know Elle Kari or that series, which also is somewhat a fictionalized photo-novella. My first thought is to put the entire series in the bibliography under the first publication in 1951, index all the authors and photographers, but not do 15 individual entries under each year one of the books in the series was issued. Thanks for pointing these out to me. I love your blog, by the way: https://onthisdateinphotography.com/.