The British artist Tacita Dean (b. 1965) happens to be one of my favorite contemporary artists.Winner of the 2006 Hugo Boss Prize (and hence a 2007 exhibition at New York’s Guggenheim Museum), her work is simultaneously visceral and intelligent and nearly always involves seemingly incompatible opposites.She often uses banal objects such as found photographs or common postcards to explore profound issues of life, death, history, and memory.Much of her art is based on historical or biographical research, yet chance and coincidence are everpresent factors. Since 2001, Dean has referenced Sebald in several of her works.

Tacita Dean: W.G. SEBALD (2003)

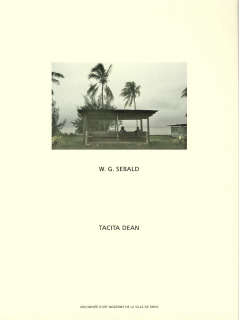

Although chronologically not the earliest piece on Sebald, her 2003 Paris catalog provides the perfect entrée to examining the connections between Tacita Dean and W.G. Sebald.In September 1999, while recording ambient sound in a bus stop on the island of Fiji for a commissioned art project, Dean found herself reading the section of Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn which deals with Roger Casement, the Irish nationalist who was executed by the British for treason in 1916.Before becoming fatally entangled in the Irish nationalist movement, Casement was best known for his service as a British diplomat in Africa.His Congo Report (1904) exposed Belgian atrocities and was probably influenced by Joseph Conrad’s great 1899 novella Heart of Darkness.When Dean read the pages in which Sebald describes Casement’s trial for treason, she realized that the presiding judge who had condemned Casement to death was her great, great uncle.

Dean reveals this startling anecdote in a slim volume entitled W.G. Sebald, which is part of a boxed set of seven softcover catalogs produced in 2003 for an exhibition of her work at the Museé d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris.The “story” that she tells in W.G. Sebald, is – appropriately – full of those coincidental moments when genealogy, personal experiences, and world events intersect with oddly illuminating results.Her story not only involves Casement, Sebald, and Dean’s own ancestors, but also the aerial bombing of Germany during World War II, the Marconi Telegraph Company, and a missing family painting by Van Gogh.Like Sebald, she punctuates her story with contemporary snapshots, family photographs, historical images, found postcards, and artless photographs of objects to create a narrative that seems to meander aimlessly toward a conclusion that finally seems inevitable. Intrigued by the Casement connection to her family, the resulting artwork is more or less a document of her subsequent research.But, like Sebald’s fiction, Dean’s art is also a semi-fictional form of documentary.

The 32-page Paris catalog is bi-lingual – English and French – and delightfully uses different illustrations in each section.Some version of this piece apparently appeared in a piece that Dean published on pages 122-136 of the Fall 2003 issue of October magazine from MIT Press (surprisingly impossible to locate second hand).

Tacita Dean: THE RUSSIAN ENDING (2001)

A second volume in the Paris boxed set of catalogs is called The Russian Ending and reproduces twenty photogravures that Dean had created in 2001.While the Paris catalog makes no mention of Sebald in connection with this work, when this series was first exhibited in the U.S. at the New York gallery of Peter Blum from December 8, 2001 to February 2, 2002, the gallery issued a four-page brochure that included a quotation from Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn, which one assumes Dean herself selected.In the quotation Sebald describes the sensations of being enveloped in a sudden sandstorm.When the whirlwind dissipates into an eerie quietude he muses: “This, I thought, will be what is left after the earth has ground itself down.”

For The Russian Ending, Dean used flea market postcards to create large prints via photogravure, which serve as treatments (complete with etched-on stage directions) for an imaginary film about failure and disaster.Jordan Kantor, reviewing the exhibition in Artforum (March 2002), called the imagery of explosions, shipwrecks, and funerals a “melancholic iconography,” which would succinctly define the writings of Sebald as well.“The Russian Ending” apparently refers to a practice in which movies were once made with different endings for different markets – the Russian audience requiring the more tragic ending.

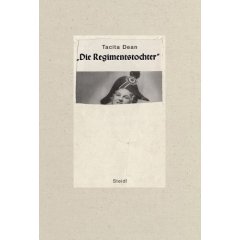

Tacita Dean:DIE REGIMENTSTOCHTER (2005)

Die Regimentstochter is a 64-page signed and numbered book designed by Dean and published by Steidl in Göttingen, Germany in an edition of 2,000 copies.The book’s title, of course, refers to the Donizetti opera known in English as The Daughter of the Regiment.The book itself reproduces a series of Nazi-era opera programs that Dean found in a Berlin flea market, all of which had sections of pages mysteriously cut out, creating a sequence of oddly evocative “found” collages.As the publisher’s website says: “Each programme gives a tantalising glimpse of a title or a face through a small window cut into the embossed cover; we recognise Beethoven, Rossini, the face of a singer perhaps.When and by whom this incision in the cover was made, very neatly one might add, even more why these disfigured programmes were kept remains a mystery. A swift search in an archive would easily show what has been removed; most likely an embossed swastika, for these performances all happened during the Third Reich. Why they were removed is left to our imaginations; perhaps an avid theatre-goer livid at the co-option of culture by the regime, perhaps someone afraid they might be misinterpreted as fascist memorabilia, while wishing to retain the memories these performances triggered.”

I have no direct evidence that Dean knowingly linked the subject of Die Regimentstochter with Sebald.Nevertheless there is a marvelous connection between Dean’s book and a short section in the “Air War and Literature” chapter in Sebald’s book On the Natural History of Destruction.From pages 42 – 45, Sebald briefly ponders the role of culture – specifically music – “in the evolution and collapse of the German Reich.” Sebald quotes a number of sources who wrote about the presence of opera and classical music – both live and on radio – in the very midst of the Allied bombing of Germany and the total devastation immediately after the end of the war.Sebald includes a photograph of war-time German audience intently, if not raptly, listening to music in a concert hall, perhaps to one of the very programs included in Tacita Dean’s book.

Jean-Christophe Royoux, Marina Warner, and Germaine Greer: TACITA DEAN (2006)

In 2006, Phaidon published a very useful introductory monograph on the work of Tacita Dean in their Contemporary Artists series.Tacita Dean discusses and illustrates many of her projects including all of the ones relating to Sebald mentioned above.In a section called “Artist’s Choice,” which recurs throughout the series, the artist under discussion is asked to make a selection from another artist or two.For her volume, Dean chose William Butler Yeats, whose 1939 poem “One-Legged Fly” is reproduced, and W.G. Sebald.Dean chose one of the most remarkable and telling paragraphs from The Rings of Saturn which begins: “As I sat there that evening in the Southwold overlooking the German ocean, I sensed quite clearly the earth’s slow turning into the dark.”What follows is a beautiful, dark meditation on landscape, dream, memory, and the power of transformation.The extract concludes: “What manner of theatre is it, in which we are at once playwright, actor, stage manager, scene painter and audience?”, which seems a near perfect description of Dean’s art.

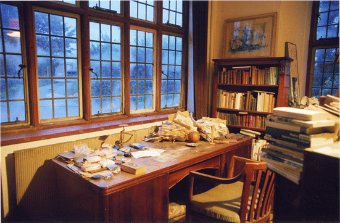

Dean continues to produce art work that relates to Sebald.As one of seven British artists commissioned to respond to Sebald’s writing and to the landscape that inspired him for an exhibition in Norwich called Waterlog, Dean has created a film on his close friend and translator, the poet Michael Hamburger.

Click here to go to my earlier post on Waterlog.

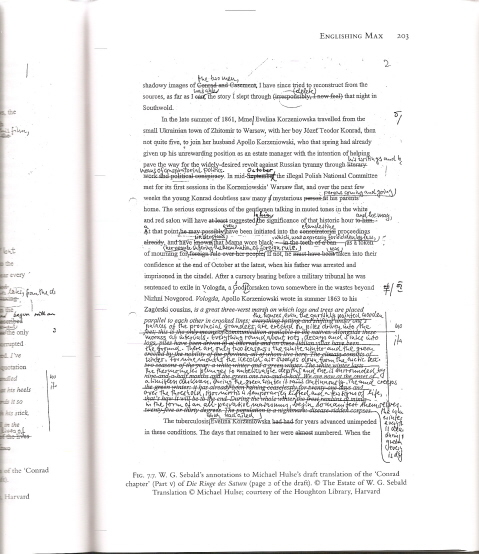

W.G. Sebald’s annotations to Michael Hulse’s draft translation of the ‘Conrad chapter’ (Part V) of Die Ringe des Saturn.

W.G. Sebald’s annotations to Michael Hulse’s draft translation of the ‘Conrad chapter’ (Part V) of Die Ringe des Saturn.