Audio CD

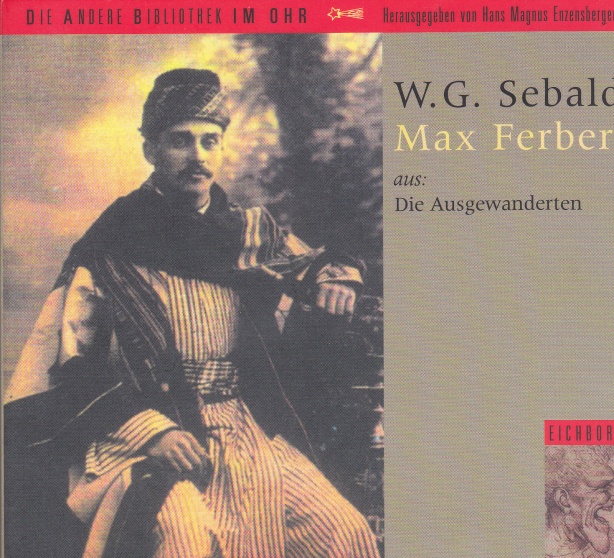

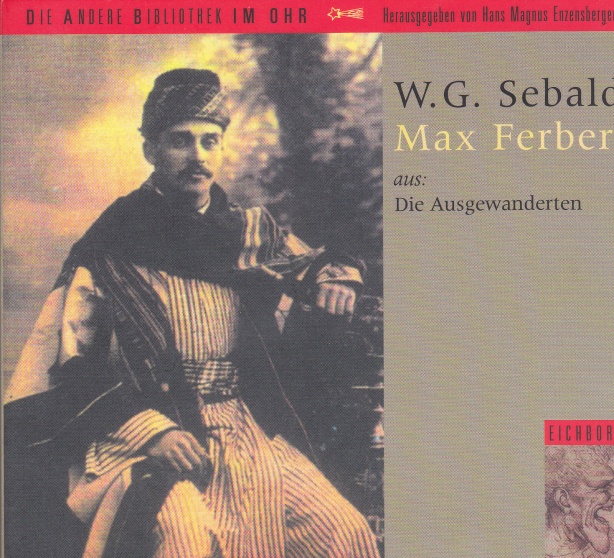

There are a couple of ways to listen to W.G. Sebald speaking or reading. Sebald personally recorded only one audio CD during his lifetime – Max Ferber (Frankfurt am Main: Eichborn Verlag, 2000). In this double compact disc set, Sebald reads in German from the “Max Ferber” section of Die Ausgewanderten.

KCRW Interview

Sebald can also be heard in a superb interview conducted on December 6, 2001 by Michael Silverblatt, host of KCRW radio’s exceptional Bookworm program. In this thirty-minute interview, held only eight days before the automobile accident that killed Sebald, he talks at length about his debt to Thomas Bernhard, who he feels was practically the only German-language author to have not compromised his writing. To be morally compromised, Sebald says, ultimately leads to being aesthetically “insufficient.” Sebald describes Bernhard’s style as a “periscopic form of writing” in that he only tells you what he sees – nothing more, nothing less – a style Sebald uses to some extent in Austerlitz. It is a great pleasure to listen to Sebald’s voice and his immaculate, slightly obsolete English responses to Silverblatt’s intelligent observations and questions. It’s worth trying to find Silverblatt’s interview with Sebald on Bookworm, if you can.

Reading at 92nd Street Y

On October 15, 2001, a few weeks before the radio interview mentioned above, Sebald gave a public reading at New York’s 92nd Street Y, which can be seen on YouTube. The video is 49:23 long. Sebald introduces his just-published book Austerlitz for about five minutes and then reads for twenty-five minutes from the section in which Jacques Austerlitz and Marie travel to the spa town of Marienbad. That selection is not only a very important part of the book, it’s an interesting one to watch Sebald read since it contains segments in both French and German and so we hear Sebald actually reading in three different languages.

That night at the 92nd Street Y, Sebald shared the stage with Susan Sontag and so they are seen sharing the question-and-answer period. Sontag is asked about her admiration for Nabokov and to elaborate on the consequences of the controversial essay she wrote for The New Yorker immediately after 9/11.

Sebald is shown answering two questions. The first has to do with his use of photographs. He explains that often the photographs precede the writing as was the case with the cover image for Austerlitz, which was “the point of departure” for the whole book. Sebald says that photographs “hold up the flow of discourse” in the text, slowing down the reader’s path down the “negative gradient” of a book. All books must come to an end, therefore the book is inherently an “apocalyptic structure.” Photographs also serve as an affirmation to the reader that the story is based in truth. But, at the same time, “pictures can be used as means of forgery” and Sebald confesses to have tampered with “not a few” in his books and he admits that he uses photographs to “develop complex games of hide and seek.” Sebald notes that historic photographs “demand” that the reader address the lost lives they represent.

The second question posed to Sebald had to do with translation and why he uses a translator. In the midst of his response, Sebald mentions that authors occasionally have to “intervene” with a translator and he hints – not for the first time – that he had to do so himself. As to why he uses a translator, he offered two reasons. He doesn’t completely trust his English and, because feels he is running out of time, he doesn’t want to spend his days translating himself. He says he “sees the horizon.” (Two months later he was dead.)

The final question was addressed to both Sontag and Sebald: What is their favorite book of the ones they’ve published. Sontag: “the last two novels” Volcano Lover and In America. Sebald’s answer is to say that “books written look like abandoned children” and so he cannot pick a favorite. But there are certain rare sections of his books that are his favorites, namely those pages that came to him “without hesitation”. Here, Sebald talks a bit about the “Il ritorno in patria” section of Vertigo, which flowed from pencil to pad.

[This post updated August 2013.]