Draining the Sea

I am a man collects corpses. I eat photographs and I am a dead man also. A tired man; a whorish man; a man who does not look back, I have only the future in front of me, no present; I am a man without history; and I am a man of despair…

Micheline Aharonian Marcom’s Draining the Sea (Riverhead Books, 2008) is the third in a trio of books that included Three Apples Fell from Heaven (2001) and The Daydreaming Boy (2004). Not quite a trilogy, the three novels each have their roots in the Armenian Holocaust.

The first,Three Apples Fell from Heaven,was a poetic, frightening, visceral book about the brutal oppression, murder,and forced exile of more than a million Armenians in what is now Turkey, circa 1917. It had no central narrator or character, but followed the fates of a number of people trapped by the upheaval. Then came The Daydreaming Boy, which took place in Beirut in 1963, with the first signs of that country’s civil unrest appearing in the background. It essentially had a single character, a middle-aged man named Vahé, who had been the product of the badly-run orphanage system created to handle the parentless children of the Armenian Holocaust. For me, Daydreaming felt like a transitional book, only half realized. Vahé was a pathetic, gross, and scarcely likable character, and he seemed a poor fit and unworthy receptacle for Marcom’s explosive, dreamy language. I found it curious that his lazy, lascivious, violent life was more the result of the orphanage rather than the distant events in Turkey which claimed his heritage and family. The third book, Draining the Sea brings us up to the end of the twentieth century and into the Americas, following an emigrant path westward across the globe. Draining the Sea also returns to the kind of blood-soaked history that we witnessed in Three Apples, only now the violence occurs during the civil conflict that erupted in Guatemala in the 1980s.

Draining relentlessly exposes us to the mind of Marcom’s narrator and it is not a pretty sight. He is nameless and unpleasant man who lives in Los Angeles and he immediately announces “I am irritable, a fat and ugly man”and “these are not stories for the faint of heart.” While he drives the streets and freeways of Los Angeles or sits morosely at home, he obsessively addresses his thoughts to a woman named Marta (“the indigenous one”), who perished in a massacre of the villagers of Acul, Guatemala in 1982. The narrator explicitly lets us know he had been sexually involved with Marta in Guatemala before seeming to have been responsible for or complicit in her torture and death. Or so it seems. Marcom’s narrator also serves as the oracular voice of the history of post-Columbian Americas. “I am a scribe, a stenographer of lust,” he says, referring to the half-millennium of bloodshed from Columbus to Guatemala. His rabid confession, full of self-loathing, is a powerful indictment of the colonization of the Americas, the failure of the American Dream, and the psyche of the white male.

And I did not intend to kill you, no more perhaps than I intended to kill and rekill the Gabrielino girls and boys (their existence) for this American man to become so: an American in his city; an idea of a man? and my ideas in my head (are they mine?) history’d from my teachers, memory’d from the boys on the playground, push my head into the dirt, tarmac, the playground view of the palms in the distance, the girls in the back row; the television blares in the background. These Americas make us and they unmake us, unmade and making you all of the time – disease, the vagrancy laws, lynching laws, blacks, white roads rules and Indians. – Do you exist, darling? And if not, may I?

He knows modern Western civilization is out of sync and his confession is also intended to be a testament to and partial restitution for this sadistic and murderous history. D.H. Lawrence and Walt Whitman are the earthy, redemptive angels that hover over this book and their words are often embedded in Marcom’s text. Here, the narrator quotes Lawrence: “We must get back into relation, vivid and nourishing relation to the cosmos and the universe.”

This book has haunted me for more than a month. The telling and retelling of acts of misogynistic sex and torture is painful to read. And I continually felt frustrated by my inability to determine if the narrator actually did these acts or “merely” imagines them, even though I know the answer is both: the narrator is simultaneously a character and the voice of history. I don’t think there is much doubt that this is precisely what Marcom intended. Through distasteful characters and unpleasant acts, she forces the reader to experience her text viscerally as well as intellectually. Her goal seems to repulse any easy reading or single interpretation. It’s a hire-wire act from start to finish, but Marcom has no second thoughts about falling off and immediately getting back on the wire. In the end, I found Draining the Sea to be the most astonishing and powerful book of this trio. (The title, by the way, comes from a statement made by Guatemala’s General Rios Montt. “The guerrilla is the fish. The people are the sea. If you cannot catch the fish, you have to drain the sea.”)

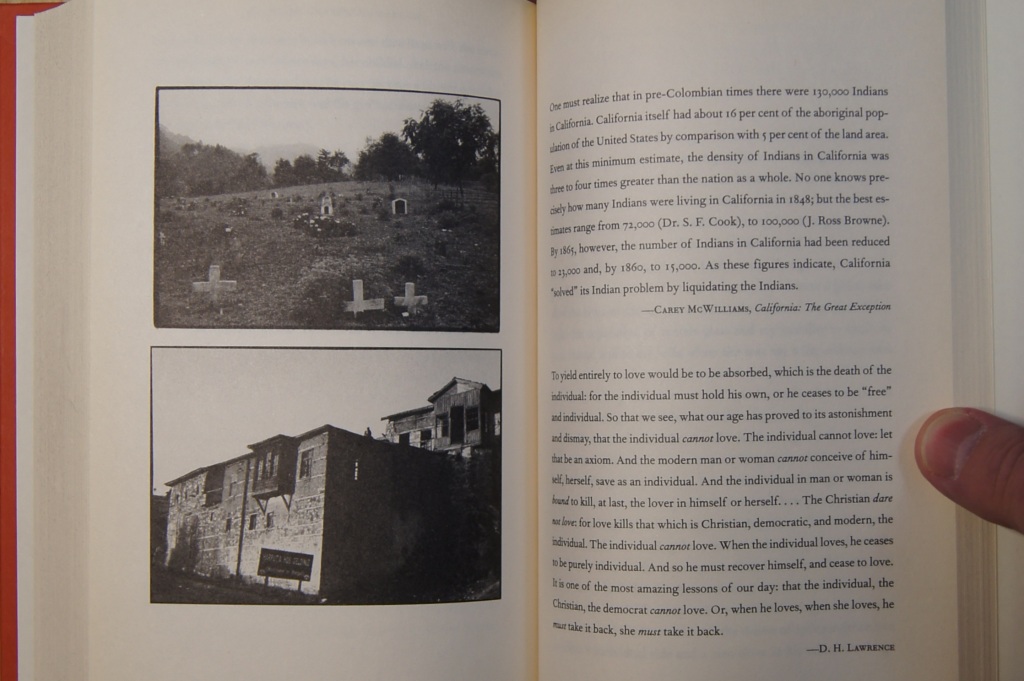

All of the books in this trio use photographs to anchor the text in history, acting as a kind of verification that there are real people and real events at the basis of Marcom’s fiction. In Draining the Sea, each of the book’s five sections begins with a pair of photographs that make linkages between “soulless” Los Angeles, the Armenian Holocaust, and the civil war in Guatemala.

“The Bone Boy, Der Zor Desert, Syria” and “The Polytechnic School, Guatemala City, Guatemala”

“Cemetery in Acul, Guatemala. Site where the victims of the massacre were killed and dumped into a mass grave. (The site was later exhumed and the victims re interred.)” and “Entrance to Khaphert (Harput), Turkey.”

“Cemetery in Acul, Guatemala. Site where the victims of the massacre were killed and dumped into a mass grave. (The site was later exhumed and the victims re interred.)” and “Entrance to Khaphert (Harput), Turkey.”

[Captions from the “List of Photographs” at the back of Draining the Sea.]