Sebald Issue of boundary 2 Journal

Readers of W.G. Sebald are in something special. boundary 2: An International Journal of Literature and Culture has devoted the entire contents of Volume 47 Issue 3 to Sebald and it’s all available online for free. Edited by Sina Rahmani , the title of the issue is “W. G. Sebald and the Global Valences of the Critical.” Here is what you can find in the issue.

Sina Rahmani, “Words, Not Bombs: W. G. Sebald and the Global Valences of the Critical.”

Sebald’s meteoric rise shines a light on the hegemonic role the anglophone literary market plays in the processes that authors and their texts undergo when they migrate from a national literary market to a planetary readership. Indeed, migration offers a key to Sebald’s oddball career and its place in literary history. Like many of the literati holy orders into whose ranks he has been admitted, Sebald’s biography is marked by a permanent departure from the land of his birth.

Uwe Schütte, “Troubling Signs: Sebald, Ambivalence, and the Function of the Critic.”

His unconventional authorial identity cannot be fully comprehended without an appreciation of the critical writings and, in turn, his transformation from scholar to writer. The most prominent feature of his work in the critical sphere is the stubbornly contrarian stance Sebald assumed toward his peers in German studies specifically and the Germanic literary establishment more generally. . . .Only when both sides of Sebald’s coin [his critical writings and his imaginative writings] are considered in concert can one begin to grasp the power and significance of his career.

Stuart Burrows, “The Roar of the Minotaur: W. G. Sebald’s Echospaces.”

I will describe the contours of this different dimension, in the belief that Sebald’s distinctive contribution to the global novel lies in his reordering of the space of representation. This reordering is both literal and metaphorical. It is literal, in the sense that Sebald’s work explores actual spaces: the pages upon which his novels are written, which become inextricable from the world being described, and the landscape being traversed, such as the Suffolk coastline in The Rings of Saturn (1998); it is metaphorical, in the sense that Sebald’s work explores a set of imaginary spaces nested within each other, those spaces occupied by his characters, who inhabit several worlds simultaneously, and those allocated to the narrative voice, which speaks to us out of a clearly demarcated yet ultimately unlocatable place.

Yahya Elsaghe, “Penelope’s Crossword: On W. G. Sebald’s Austerlitz.”

The crossword as a form has the upper hand over the rhizome as a metaphor for textuality—something it shares with other allegories of memory like a ‘wonderblock’ and ‘palimpsest’ as well as ‘signs and characters from the type case of forgotten things’.

Sina Rahmani, “The Stateless Novel: Refugees, Literary Form, and the Rise of Containerization.”

This ‘prose book of an undetermined kind,’ Sebald’s coy descriptor for Austerlitz, offers an instructive lesson about the novel of the global era, which has become a formal container providing refuge to any and all narrative and literary forms. In the same way that the shipping container is completely unconcerned with its own contents, Austerlitz furnishes us with incontrovertible evidence that in a stateless era, the foundational distinctions between written and visual, fiction and nonfiction, poetry and prose, analytic and creative, and, as Stuart Burrows points out in his contribution to this issue, verbal and written have been eradicated.

Isa Murdock- Hinrichs, “Adaptation, Appropriation, Translation: Sebald on the Silver Screen.” Murdock-Hinrichs examines two films based upon books by Sebald: Grant Gee’s Patience (After Sebald) (2012) and Stan Neumann’s Austerlitz (2015).

Gee’s deliberate transformation of the visuals in the film into a maze of images whose uniform intelligibility is obscured represents a translation of Sebald’s disjunction between text and visual.

. . .

Neumann highlights the various qualities of visuals as he weaves static images, alternative film stock, and printed materials into the film. The camera is the translator of the narrative of the literary text by further portraying the instability of systems of meaning.

Global Critical Forum

“This special issue of boundary 2 has sought out translations of articles and reviews of different Sebald texts. The Global Critical Forum highlights the array of responses and mixed feelings Sebald solicits in different national contexts.”

Nissim Calderon, “Sebald or Gevalt?” [Originally published in Yedioth Ahronoth (Tel Aviv, Israel) in 2009.]

Sebald’s Rings of Saturn is a particularly bad text; bad precisely because it features his idiosyncratic and excellent style but lacks the content to justify it. It is an empty style, like the painter Salvador Dalí, who in his youth paved the way for art’s new surrealist path but in his later years became a serial producer of the “Dalí style.”

Rodrigo Fresán, “The Sebald Case.” [This is a slightly revised translation of an article published in Letras Libres, a Spanish- language monthly literary magazine published in Mexico and Spain, in July 2003.]

In the here and now, the departed Sebald is very, very interesting for those who have survived him, for the many that quietly concede in hushed tones, perhaps out of fear of falling victim to a Pharaoh’s curse, his some-what exaggerated prestige, and for the many more that swear by his divine name they continuously invoke in vain—to remain in good standing and to have a ready response to the question, What are you reading at the moment? Sebald serves, functions, protects, and refreshes best, and is so fashionable, so useful for the nouveaux riche of the intelligentsia. Sebald is practical and legible; he grants a certain prestige to his user and his consumer. Sebald is not only learned but also produces the agreeable effect, or impression, of cultivating and producing evangelical astuteness.

Maria Malikova, “Witnessing the Past in the Work of W. G. Sebald.” [This article was published in 2008 in Отечественные записки (Notes from the Home-land: A Journal for Slow Reading).]

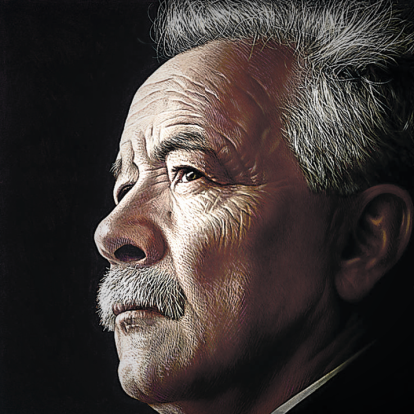

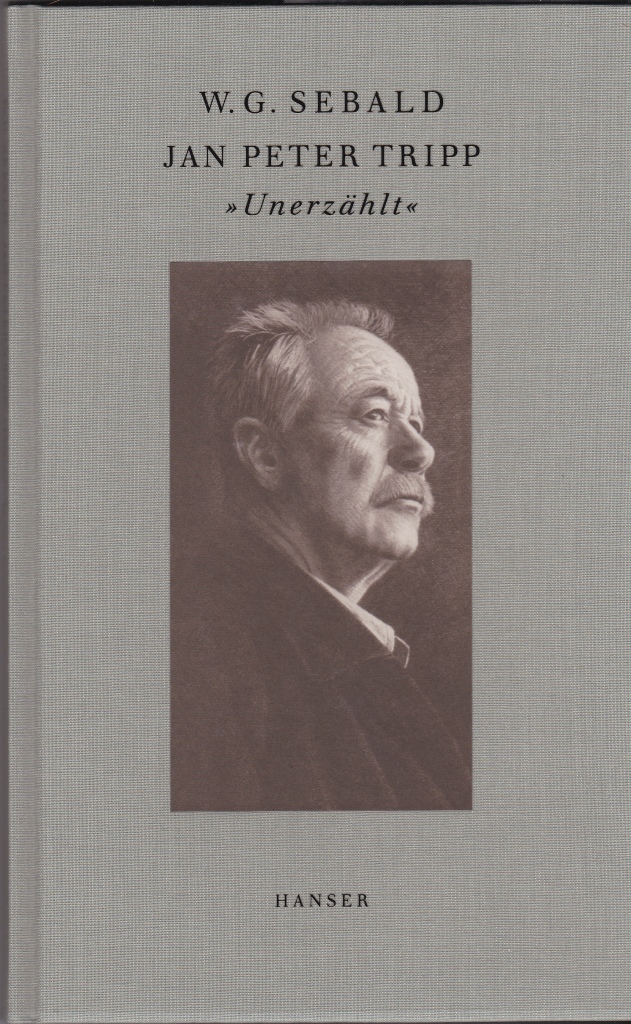

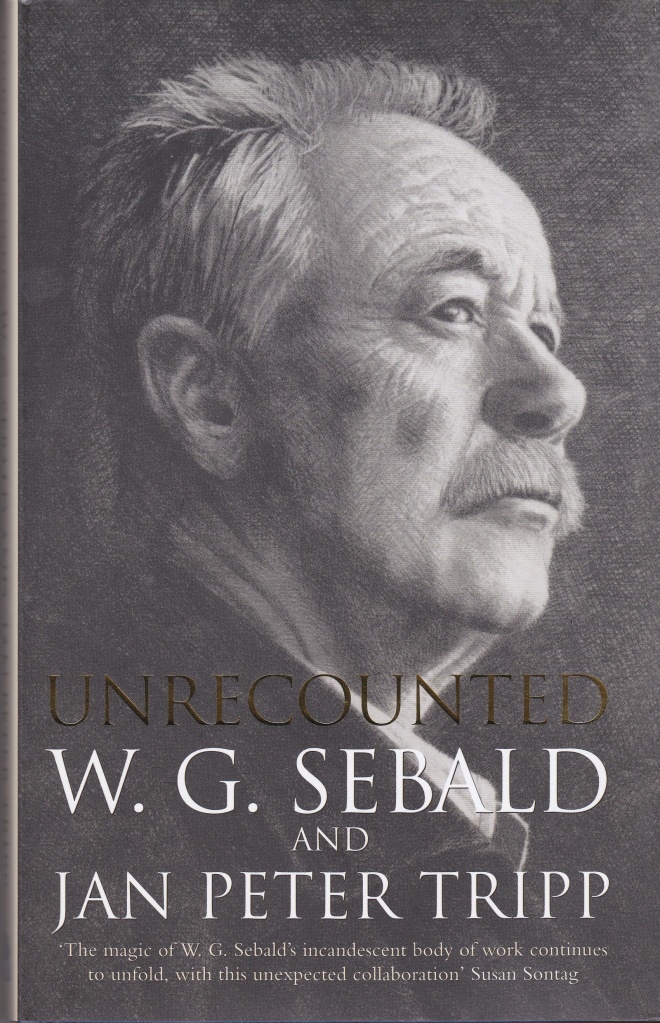

Artist and photographer Jan Peter Tripp was a key figure in the career of German writer and critic W. G. Sebald. . . .[in Sebald’s 1998 essay on Tripp] he provides a graphic display of the evolution of the role of the visual in [his] poetics from photographs of objects, faces, landscapes, architecture, and paintings, to depictions of the very organ of sight, the mechanism of vision: eyes, fixed directly on the reader- viewer, demanding a reciprocal gaze, an ethical reaction.

He Ning, “The Bricolage of Words and Images: W. G. Sebald’s Austerlitz.” [This article is translated from a Mandarin article 文字与照片的拼接—评W. G.赛巴尔德的《奥斯特里茨》, which appeared in Trends of Foreign Literature (《外国文学动态研究》) in 2012.]

Austerlitz’s method of piecing together memories through recategorizing the photos he has into a spatial rather than temporal order reifies what I call a retroactive act of bricolage, an innovative way to reconstruct the protagonist’s own narrative. Inspired by the art of photography, he seems to find a psychological equilibrium between his defense mechanism (i.e., selective amnesia) and his desire to recover and rediscover his own identity.

The issue concludes with an article not about Sebald but one closely aligned with his lectures on “Air War and Literature,” included in On the Natural History of Destruction. Sina Rahmani conducts an interview with Emran Feroz entitled “Death from Above: An Afghan Perspective on the US Drone War.”

boundary 2 has an unusual editorial statement:

The editors of boundary 2 announce that they no longer intend to publish in the standard professional areas, but only materials that identify and analyze the tyrannies of thought and action spreading around the world and that suggest alternatives to these emerging configurations of power.