Adam Scovell’s “Nettles”

In Nettles (Influx Press), his third novel in the last four years, Adam Scovell brings new life to the well-trod theme in British literature of being bullied at school. His narrator is revisiting the Liverpool area, cleaning his boyhood possessions out of his childhood home. He’s also revisiting vivid memories of twenty years ago when his school days were spent trying to dodge Him—always with a capital H—the nameless bully who attacked him on his way to the first day of school, whipping him mercilessly with stinging nettles, and who proceeded to make his life miserable for the remainder of the school year.

It was the first day of term when He whipped my thin legs with nettle stems. The sun was glaring behind the clouds, and I knew then that I would have to kill Him. I did not know how or when, but as the stings lashed and my body quivered with pain, His fate was sealed, cast in marble.

The narrator, like nearly everyone else in the novel, has no name. He uses his wiles to try to avoid the bully and his gang as much as possible, but he also vows to himself that he will withstand whatever punishment they give him. But after one serious fight with the bully in the marshlands at the edge of the school grounds, he has to be rescued by a teacher.

A teacher dragged me through the building with my head held backward, my shirt dotted with bright red droplets, limping towards somewhere with first aid equipment,. I took pleasure in imagining the boys talking together about my new adulthood. I could not contain myself and I cackled viciously.

My body turned to hogweed.

I was the marsh and the stone.

Laughing.

The walls blurred and the teacher faded into ragwort and lichen

I drifted from the world and fainted in the chair they propped me up in.

I was utterly pathetic.

Eventually, a plan forms in the narrator’s mind. If he can lure Him to a nearby area called The Breck, a well-known and somewhat dangerous climbing spot, perhaps some sort of accident can be arranged. The Breck is famous for being the place where the first British man to ascend K2 had honed his skills as a young man. [If you are curious, you can see The Breck here.]

In the end, it turns out that we, as readers, are here to help judge the narrator, not the bully or anyone else in the novel. We are left to decide if the narrator interpreted his childhood correctly. The narrator is basically the only character with interior dimensions in the book. He seems incapable of viewing anyone else with any depth. Both of his parents are present, but neither becomes a three-dimensional person on their own. And the bully remains as elusive as if we were talking about the devil himself. All we get of Him is the physical description of “His severely shaved head and His bulky persona.” The bully and his disciples repeatedly beat up the narrator for pages on end without ever being described or characterized.

At first, it was Scovell’s “revenge” plot that made me want to keep read reading Nettles, but inexorably the narrator’s true plight—the one with his family—took over in importance. During his return visit, as the narrator looks back on this period in his youth, he began to ask himself if some of the assumptions he had made at the time about his family were correct.

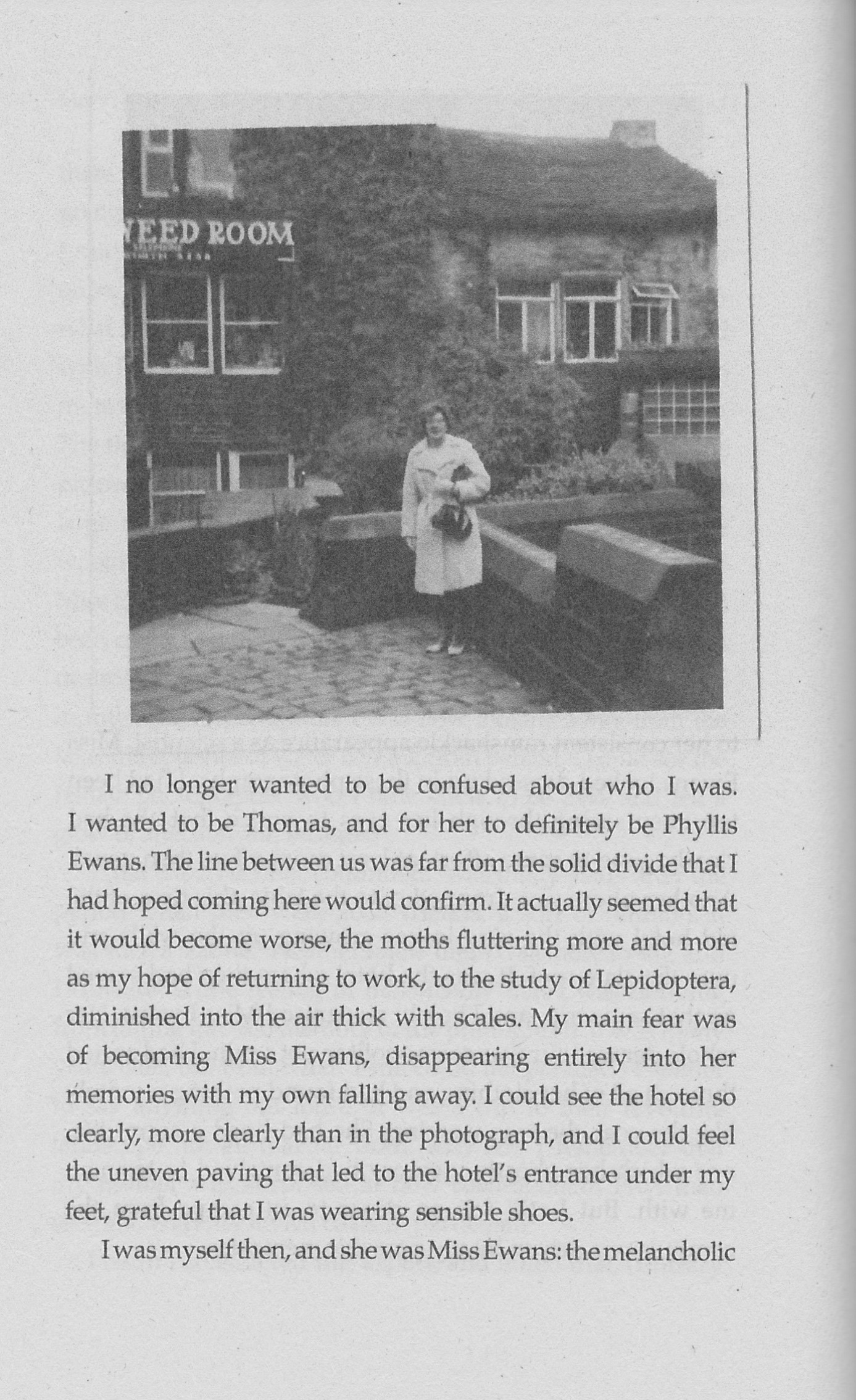

Throughout his visit home, the narrator takes Polaroid photographs of the sites that were memorable to him in his youth. To us they look like square, rather blurry amateur snapshots of boring locales. As if to demonstrate how much these photographs mean to him, the only character in the book that the narrator names is Ellen, the “talented fashion photographer” who lends him the camera. But his photographs turn out to be bitter disappointments. At first he thinks he sees traces of the past in them, but then he decides, as he does with one photograph, “there was nothing there now but stone and memories.” The real story lies elsewhere.

Ironically, it is his mother who provides him with the one photograph that stings. As he is heading back to London, she hands him a photograph. . . It was more human than the reflection in the visor mirror. My eyes were light and carefree then. I couldn’t recognize the boy anymore. I would tear the photo in half later, unable to allow it to exist. It made me feel simultaneously alien and homesick.

The top half of this ripped photograph appears at the very beginning of Nettles, the torn bottom (and larger) half appears at the very end. Buried in Nettles is a bitter family story that stings the narrator far worse than the bully from his school days. It’s fascinating to watch Scovell expertly play the bullying story and the family saga against each other, until one strand emerges holding the narrator’s past at gunpoint.

With each of his three books, the way in which Scovell has deployed his photographs has become more and more tangential to the story as his writing has become stronger. In Nettles, I would argue that the only photograph that is really necessary to the plot is the torn image that we see at the front and back of the book. The other images are, as the narrator admits, “failures,” used only as evidence that there was no longer anything meaningful to him in those places. But even the torn image is one that many writers would verbally describe and then omit from their novels. I look forward to seeing how Scovell deals with photographs in his novels in the future. Here are my reviews of Mothlight (2018) and How Pale the Winter Has Made Us (2020). Nettles is just out from Influx Press this week.