Recently Read: Michelle Bailat-Jones & Olga Medvedkova

Michelle Bailat-Jones. Unfurled. NY: Ig Publishing, 2018.

Olga Medvedkova. Going Where. London: Sylph Editions, 2018. The Cahiers Series 33.

Neither of us realized we had been living in a borderland all that time, a place where rules are too often unspoken, never declared. We didn’t understand there were passports and checkpoints involved. And that not all three of us would make it through.

So begins Michelle Bailat-Jones’s second novel Unfurled, whose narrator Ella is about to have one very bad week. Ella is a veterinarian, highly sensitized to the health and needs of animals, but prone to ignoring those things that make her own well-being precarious. Almost simultaneously, Ella’s father is killed in an accident and she discovers she is pregnant. What Bailat-Jones does here is to flip the obvious scenario, which would be to close down Ella’s past and open up her future. Instead, the death of Ella’s father reveals that there were secrets he had hidden from her throughout most of her life. And bearing a child is not a future that she envisions for herself. She decides she will eventually terminate the pregnancy.

Ella’s mother, as we see in flashbacks, was mentally unstable and walked out of her marriage when Ella was ten, leaving Ella and her father to build a new family of two. Or so Ella thought. For years, she has walled off any memory or hint of emotion about her mother except anger and blame. But with her father’s death she learns that he seems to have secretly been in touch with her mother for years. And then she learns he owned a cabin, which is now Ella’s. Did her father have secret rendezvous there—perhaps with her mother? Ella’s instant and stubborn reactions to these two life-changing events also begins to threaten her marriage with Neil.

What I found fascinating about Unfurled was the way in which revelation and concealment act like two tectonic plates that are approaching each other and vying to dominate. As Ella hunkers down within her fear and mourning, she seems to notice every little thing within her frame of vision: “Neil’s hands on the steering wheel, my boots on the floor, my knees shaking, my hands fluttering around and over the pocket of my jacket with the torn photos.” Ella notices exactly how long certain actions take, how far she has to walk, but she won’t acknowledge (or share with the reader) the core mystery of her mother’s departure many years before. By the end of the book we have learned a bit more, but not everything is revealed.

Ella and her father, who had been a ferry boat captain, share a deep love for sailing, allowing Bailat-Jones to use the language of sailing as a metaphor for the way in which Ella navigates her life. She writes with such emotional intensity that reading Unfurled suddenly seemed like the most urgent thing I needed to do.

Ω

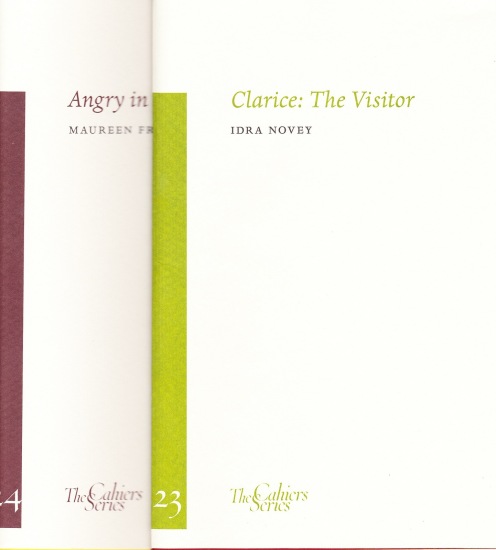

Every few months or so I look forward to the next number of The Cahiers Series, which is co-published by the Center for Writers & Translators at The American University of Paris and Sylph Editions in London. Since 2008, there have been thirty-three publications in the series, each of which is a beautifully designed combination of writing and imagery. I’ve written about a number of previous issues, and the newest Cahier is equally terrific. Going Where is a series of five brief stories by Olga Medvedkova, a Russian writer and art historian who lives in France. Each of her stories is named after the city in which the narrative takes place: Palermo, Athens, Venice, Lisbon, Jerusalem.

There’s an aura of both strangeness and estrangement in each story. The act of traveling disorients her characters, forces them into unfamiliar encounters, and provokes rash decisions. Each story is the encapsulation of a persona on the verge of doing something out of character. Here is Malvina Süstirn, a young archaeologist visiting Athens and about to sleep with a man for the first time:

The separation of the human race into two sexes did not make much sense to her. She belonged to a university world made up not of men and women but of colleagues, all of a certain neuter gender . . . She noticed others forming or breaking up their couples the way one observes the life of ants or frogs; it did not concern her. And, suddenly, this young man with the princely name pleased her. He belonged to the opposite sex, of course, but as if accidentally. Just as she, superficially, resembled a girl.

If I am not mistaken, this is Medvedkova’s first appearance in English and I can’t wait to read more by her. Her stories are translated by Richard Pevear and are accompanied by photographs of small brass houses made by the Japanese artist Hana Sakuma.