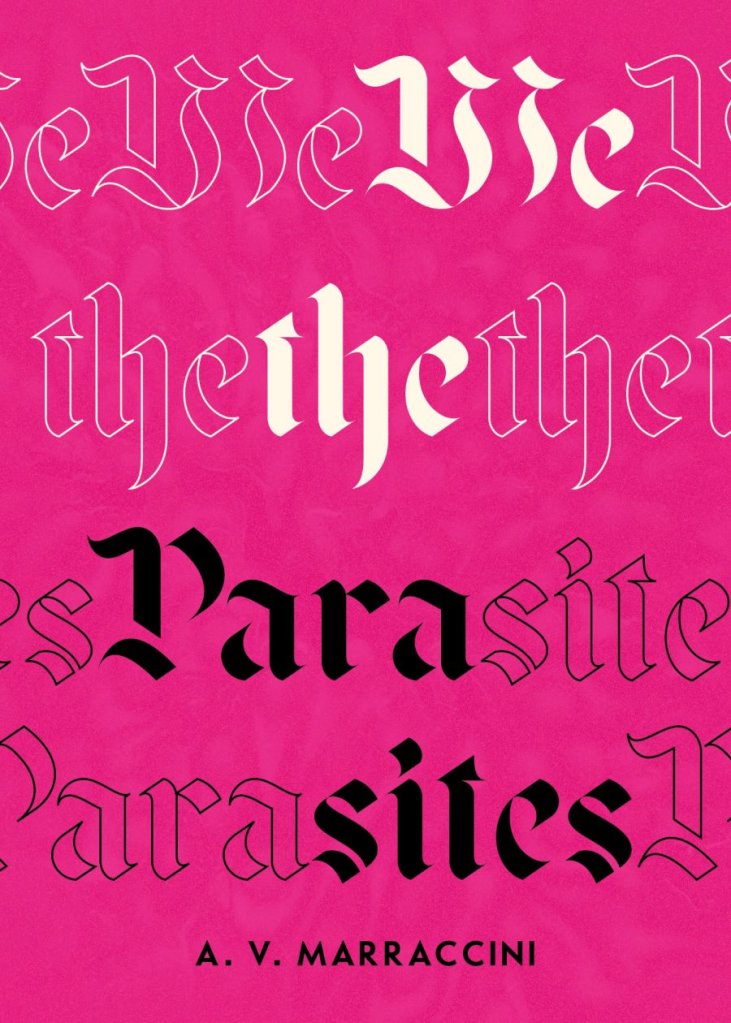

The Parasite

In her new book We the Parasites, from Sublunary Editions, the critic, essayist, and art historian A.V. Marraccini really stages an entrance. She begins by explaining the pollination of figs by female wasps. It’s a form of parasitism called mutualism, Marraccini tells us, “because the fig and the wasp need each other to produce.” But on occasion, instead of pollinating the fig, the female wasp crawls into a female fig and dies there, only to be “absorbed by the growing flesh of the fig.”

“I’m the wasp,” Marraccini declares on the next page, “I burrow into sweet, dark places of fecundity, into novels and paintings and poems and architecture, and I make them my own. I write criticism.”

The critical gaze is also erotic; we want things, we are by a degree of separation pollinating figs with other figs by means of our wasp bodies, rubbing two novels together like children who make two dolls “have sex,” except we’ll die inside the fruit and someone else will read it and eat it, rich with all the juices of my corpse. This is an odd but sensuous thing to want. And though the male-female figs exist, and the male-female wasps, the whole process, the generative third body in the dark recesses of the inverted flower, is somehow queer. Criticism, too, is somehow queer in this way, generative outside the two-gendered model, outside the matrimonial light of day way of reproducing people, wasps, figs, or knowledge.

And so, three pages into her book, Marraccini has let the reader know that there is a completely new kind of critic in town. We the Parasites reads a bit like a chatty but erudite essay that revels in the world of usually unwelcome creatures. She talks about her morning coffee and her London walks, she rants about one of her previous university professors (her Chiron), and she lets us in on her hopes for a transatlantic love affair (the Girl from Across the Sea). But she also happily name drops and quotes from the ancients, including Aristotle, Theocritus, Homer, and a half dozen others. (Let’s just say that it quickly becomes clear that she really knows her way around the ancient Greek and Roman world and medieval European history). What Marraccini does in this book is elucidate her critical platform, so to speak, and then give us some demonstrations of her work in action. Her primary interests here are the poets W.H. Auden and Rainer Maria Rilke and the artist Cy Twombly, especially several paintings he made which have, not surprisingly, themes based in the ancient world: The Age of Alexander, 1959-60, and the ten-part painting Fifty Days at Iliam, 1978.

What becomes clear very quickly is that there is no protective wall between her professional life and her personal life. When she walks through the park, thinks about a girlfriend, or basically does any daily activity, she thinks about the ancient writers and she thinks about poets and painters. And when she reads poetry or looks at art, she thinks about the people she knows and her memories of childhood. “I see The Age of Alexander when I close my eyes at night now, and when I am out in the small hours, supposedly running.” When she watches a Spanish heist show on Netflix, she thinks of The Age of Alexander. When her doctor advises that she take iron supplements, she thinks of Hesiod, who lived in the Iron Age. I can’t think of another critic offhand other than Gabriel Josipovici whose first instinct upon dealing with the modern is to think about the ancients.

“I cannot write a disinterested review,” Marraccini wrote in a piece about Marina Abramovic at Hyperallergic. As she fleshes out her critical platform, she vectors for us the kinds of things that interest her, and establishes an ideological DNA strand for her writing. And she makes clear that she cannot and will not remove the personal from the critical. This is why so many of the pieces of writing listed on her c.v. are essentially essays.

She also wants us to know that she can be a “bad girl” type of critic. (More than once she made me think of the British artist Tracey Emin, who makes frank, confessional art about her body, her love life, and, currently, her health.) “One of my bosses told me yesterday that if I wanted him to promote me for jobs in the academy. . . I was supposed to be NICE. . . This command of niceness, of course, instead, made me want to be disgusting, untouchable, speaking dark argots in corners slick with grime.”

I grow prolix and long with sacs full of eggs, made from the nutrient slop of everything I see and hear and read. I wag my body, my segments, and it is a tongue and these are its words, asshole words I have stolen like a petty thief, words I cherish because they are not agreeable, but somehow wretched and ready to disseminate and breed.

As the title suggests, the book is filled with references to parasites, tapeworms, mosquitoes, ticks, and a host of illnesses. Marraccini is attracted to the things that gross most people out, and she uses that to great effect, somewhat in the style of the transgressive American filmmaker John Waters.

In the final part of We the Parasites, Marraccini puts it all together for us and gives us an extended essay that draws on Twombly’s painting The Shield of Achilles from the series Fifty Days at Iliam, Auden’s poem “The Shield of Achilles,” and the eighteenth book of The Iliad, which is mostly an ekphrastic description of Achilles’ shield. From these works, she writes about the confusion of rage, love, and sorrow that afflicts Achilles after Hector kills his close friend Patroclus in battle and strips him of the armor that Achilles had lent his friend. Before returning to the battle where he will avenge Patroclus’s death by killing Hector, the god Hephaestus provides Achilles with a stunningly decorated new shield.

She may have titled her book We the Parasites, but Marraccini is clearly one of a kind. Last fall, she took up the position as critic in residence at the Department of Interdisciplinary Media, NYU Tandon, in Brooklyn. In August, 2023, she wrote about returning to America after years of living abroad. “I am coming back to America partly because of the art criticism I write about NFTs. Are you ready to hate me yet?” I guess I shouldn’t be too surprised to see that the critic who loves parasites and the ancient world should be fascinated with non-fungible tokens, those oh-so dubious bad boys of the ultra-contemporary art world. This is a short book of only 139 pages, but each page gave me so much to think about. After a second and a third reading, I think my brain has been subtly rewired.