Language, Unmoored

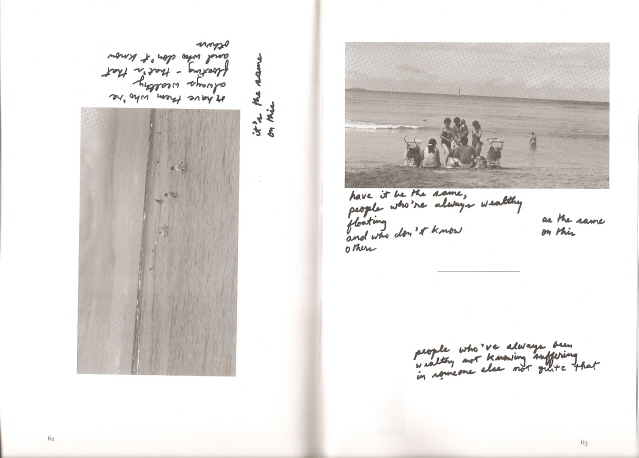

Of all of the one hundred or so books of photo-embedded fiction or poetry that have read, undoubtedly the most perplexing and resistant have been those by the poet Leslie Scalapino, who died in 2010. Crowd and not evening or light ((O Books, 1992) reproduces scraps of paper with handwritten texts and snapshots of beach and ocean scenes. When I wrote about this book earlier in a post called “Some Assembly Required,” I speculated that “what Scalapino often does in her poetry is force language into the process of losing its anchor in context, letting it start to float free.” The Tango (Granary Books, 2001) is a book-length poem that consists of a poetic text and photographs by Scalapino and other kinds of artworks by Marina Adams. It actually began as a gallery exhibition in New York City in 2001, before being adapted into book form. Scalapino’s text consists of fragments that frequently repeat and morph, along with a liberal and idiosyncratic use of typographical marks. To further complicate the reader’s task, her text, at first glance, seems utterly unrelated to the photographs of Tibetan monks mingling, talking, and dancing in a monastery courtyard. Earlier, I concluded that “Scalapino’s real subjects are language and communications and what it means to be social beings” and that she was “someone who likes to takes complicated mechanical watches apart to see how they tick.”

Fortunately, Magnus Bremmer tries to sort all of this out in his essay “Out of Site: Photography, Writing, and Displacement in Leslie Scalapino’s The Tango,” which appears in the new volume of essays that I have written about multiple times since mid-September, The Future of Text and Image: Collected Essays of Literary and Visual Conjunctures (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012). To Bremmer, the text in The Tango is “striking in its sheer density, the syntactical complexity of its language” and for its surprising “shortage of visual descriptions.”

Scalapino’s photo-texts are characterized by a sense of “writing against” the image. The images in her photo-texts bring objects, events, and places to the literary text that the writing does not simply attest to or authenticate.

In his eyes, “the juxtaposition of photos and texts… enables certain readings/viewings, but in the end delivers closure to none.” Bremmer’s dense essay covers a lot of territory and infuses no small amount of Foucault and Barthes into the mix. But in essence, he seems to be saying that Scalapino doesn’t give the photographs and texts a predetermined relationship to each other. They don’t explain or illuminate each other in any way that we typically expect words and pictures to interact on the page. Instead, the reader is given the assignment of providing ever-shifting contexts with each reading. “Scalapino’s poetry presents an incessant, subversive process of locating the self in writing.” I take the use of “self” here to mean not just Scalapino the writer, but all of us as readers. I suppose it could be said that the reader must always be in the process of locating himself or herself in the text during the act of reading – no matter what the text. It’s just that here we are confronted with an artist who makes the tangled nexus of language and meaning the explicit concern of her poetry. Here’s the opening of the final section of The Tango.

The Tango – ‘night’ any night is can’t

(Astor Piazzola’s tangos: the tango is relentless. The embrace

– a couple? – entwining goes and goes. It skips, jumps

ahead of a horizon – itself – resuming. The tango is a

hopscotch ‘ahead’ of them, a couple, it’s for convenience of

maneuver, it’s for intense love.)separation the that’s, outside as same the interior only

(separation) that’s – , separation a to illumines‘live why?’ – one some on dependent – illumines – no place

Bremmer points to the indexicality of Scalapino’s work as both the source of confusion for the reader and a key element in her strategy of showing us how language works unmoored from context. The Tango is full of pronouns – he, they, it – and references to direction that cannot be clearly linked to anything else in the text or in the images. When I first read Scalapino, I was tempted to think of her language as abstract, like a solid wall of words stripped of or resistant to meaning. Slowly, however, her work has evolved for me. It seems more organic. It helps to read the work out loud or to listen to Scalpino read and one suddenly wonders if this isn’t somehow related to the way the brain works, using bits of language and images to build up meaning, not in a linear fashion but simultaneously, stutteringly, from many directions.

Many links to Leslie Scalapino reading can be found at the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Programs in Contemporary Writing website.