Pandemic Time

Without appointments and concerts, without events and other things that remind me of the date, I find myself looking at the calendar more often, trying to fix in my mind a place to lodge myself in the stream of time. Is it Sunday or maybe Monday? But to be honest, the calendar that seems more like the true pandemic calendar is the one that hangs on my wall made by the German artist Hanne Darboven in 1971 as a gift for one of her collectors, which I acquired years ago. It’s a calendar for the year 1972 and Darboven carefully filled all of the spaces surrounding the actual calendar with wavy black lines. It doesn’t seem like much at first, but it’s connected to a large body of work she did with calendars over several years.

When I saw some of the calendar works by Darboven (1941-2009) for the first time I was struck by the fact that they depicted the way I felt about time, about eternity slowly unfolding before me. The cinematic version of time passing, which often shows a succession of calendar pages disappearing off the screen, blown away by the breeze, was never how I understood time. For me, it’s the constant repetition, the endless mimetic motion of the hand up and down, left to right, the same gesture day after day after day. That feels like time.

These obsessive, wavy lines became one of Darboven’s signature marks, one that she used for years in scores of works. Each line is a simple unbroken set of waves that appears to have been made with a medium-tipped black marker. The line rises and falls, undulating like a word comprised only of the lower-case, un-dotted letter “i” or an endless line of the letter “u” written in cursive, leaning slightly to the right. This line is repeated time after time, filling the allotted space. It’s a recognition of the underlying sameness of every cycle of day and night, followed by another day and night. But it also feels like a form of penance (I will not chew gum in class anymore. I will not chew gum in class anymore. I will not . . . ) When I was young, the very idea of eternity (and eternal life) frightened me unbelievably.

Darboven’s wavy lines remind me of something from the early pages of Samuel Beckett’s Molloy, when the title character watches from his mother’s house as two men—who he calls A and C—walk toward each other in the distance.

The road, hard and white, seared the tender pastures, rose and fell at the whim of the hills and hollows. The town was not far. It was two men, unmistakably, one small and one tall . . . At first a wide space lay between them. They couldn’t have seen each other, even had they raised their heads and looked about, because of this wide space, and then because of the undulating land, which caused the road to be in waves, not high, but high enough.

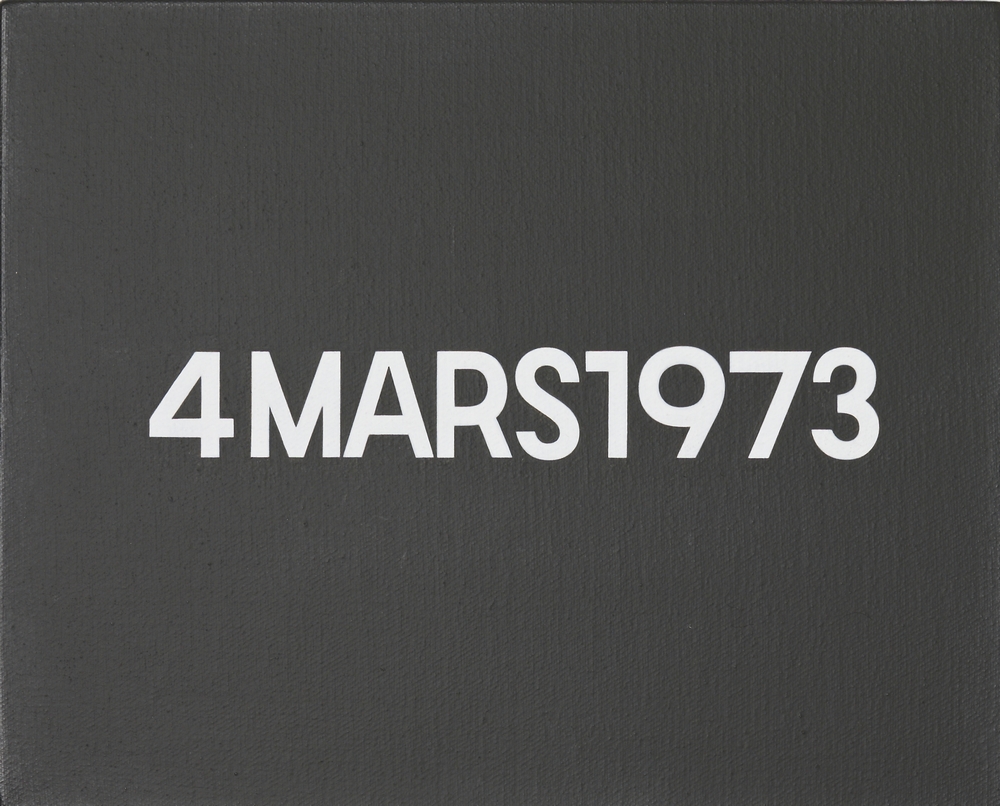

The other artist whose sense of time matches this pandemic was the Japanese artist On Kawara (1932-2014), especially his Today Series of paintings (also called his Date Paintings). Each of these black-and-white paintings conveyed only the current date and he had a self-imposed requirement that each of these paintings would be completed on the day in which he started them. In addition, the language and format of the date had to conform to the country where he was staying at the time. Upon completion, the painting would be housed in a box accompanied by a daily newspaper from date and the city where the painting was made. These are paintings for days on which there appear to be no past and no future.

On Kawara also published a two-volume limited edition book called One Million Years. The first volume, Past, is dedicated to “all those who have lived and died,” and covers the years from 998,031 BC to 1969 AD. The second volume, Future, is dedicated to “the last one,” and begins with the year 1993 AD and ends with the year 1,001,992 AD.