Typecasting Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn

W.G. Sebald’s books present a number of challenges to book designers, not the least of which is the inclusion of images (some of them deliberately of very poor quality) within his texts. And then there is the challenge to the book jacket designer, who must cope with the fact that there is no identifiable topic to Sebald’s prose and poetic texts.

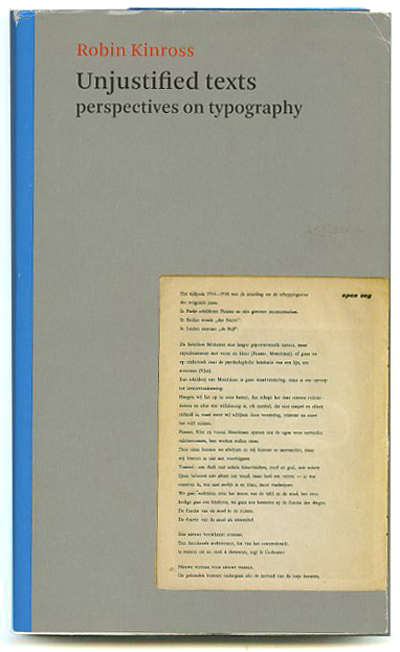

Typographer, author, critic, and editor Robin Kinross addresses these issues in a wonderful essay in his book Unjustified Texts (London: Hyphen Press, 2002). His essay, Judging a Book by its Material Embodiment: A German-English Example (pp. 186-199) opens with some reflections by Theodor Adorno on the commodification (i.e. consumerification) of books in the twentieth century, then proceeds to a brief history of Die Andere Bibliothek, the important series of books edited by Hans Magnus Enzensberger. Sebald’s first three prose works were released as volumes in this series.Founded in 1985 as an idealistic collaboration between the editor Enzensberger and the publisher Franz Greno (who published Sebald’s most exquisite book Nach der Natur in 1988), the series was sold to Eichborn Verlag in 1989, although Greno continued to be in charge of book production.

Kinross praises the production values, the materials, and the attention to details that typify Die Andere Bibliothek, zeroing in on Sebald’s Die Ringe des Saturn. But more importantly, Kinross suggests that Die Andere Bibliothek is committed to the book as object rather than the book as commodity:

The Andere Bibliothek was, and still is, an attempt to publish books of real content in a form that had distinct material quality, and which, in sum, resisted the apparently irresistible processes of commodification.

Kinross makes a direct physical and aesthetic comparison between the German edition of Die Ringe des Saturn (1995) and The Rings of Saturn as published in Great Britain by Harvill in 1998. He examines the paper, binding, typography, and other physical characteristics of both books, as well as a comparing the placement Sebald’s photographs in both versions. The bottom line, in Kinross’ mind, is that he Harvill edition “betrays the work,” and in reaching this conclusion he feels that the comparison:

tells us something about present-day literary culture in the two countries [and] something about Sebald’s enterprise as a writer.

Anyone interested in books and book production will enjoy the entirety of Kinross’ book. On topics ranging from Jan Tschichold to the layout of the Dutch telephone directory, Kinross brings an erudite intelligence, a sharp eye, and high standards to the discussion.