Photo-Embedded Poetry – Where To Start

Poets have been placing photographs in their books since the end of the nineteenth century, often in the form of illustrations. On occasion, the visual materials that poets have included are actually an integral part of the book’s poetry. In these volumes of poetry, the photographs (or other images) are part of and essential to the text.

On my page called Photo-Embedded Fiction—The Seminal Works, you can see the handful of books that I feel have been the most influential for other writers and also for building an audience of receptive readers for this hybrid form of the novel. For a variety of reasons, there isn’t a similar situation in poetry. Looking back over the long history of poetry with embedded photographs, there simply aren’t single titles that have acted as powerful influences on other poets or readers. If any book gets mentioned or talked about with any regularity, it would probably be one of two books by Claudia Rankine, Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric (2004) or Citizen: An American Lyric (2014). Both of these are books of poetry filled with images—photographs and reproductions of artworks—and both found a readership far beyond the traditional bounds of poetry fans. But they are both so recent that any influence they have is limited to the last few years.

Instead, in poetry, over the last several decades a few poets have produced title after title of poetry volume filled with embedded photographs. So, it makes more sense to speak of a handful of poets than a handful of books. I picked five poets—Susan Howe, Leslie Scalapino, Suzanne Doppelt, Claudia Rankine, and Eleni Sikilenos—whose work probably created the acceptance which exists now for this kind of hybrid poetry. So, I suggest you start with them, along with a very short list of additional titles that are personal favorites of mine.

Susan Howe. Howe, a graduate of the Boston Museum School, was originally a visual artist, publishing her first book of poetry in 1974. Many of her books include photographs, but the images are often of other texts. These texts are usually handwritten or reproduced from other books, and sometimes they are even folded or cut up. In one of her poems in Concordance (Grenfell Press, 2019), she wrote, “I have composed a careful and on one level truly meant narrative and on another level the Narrative of a Scissor.”Start with either The Midnight (New Directions, 2003) or This That (New Directions, 2010). Here’s a link to all of my posts about Susan Howe’s books.

Leslie Scalapino. Scalapino, who died in 2010, was a relentlessly experimental writer who often employed photographs, unusual typography, and handwriting in her poetry. The book to start with is Crowd and not evening or light: a poem. (O Books/Sun and Moon Press, 1992), a book-length poem with seventy-six black and white snapshots. It’s a book that constantly allows the reader permission to reassess the very nature of meaning itself. Scalapino doesn’t offer the reader any easy connection between the photographs and the text in her books. She leaves the task of determining meaning up to the reader. I’ve written previously about Crowd and not evening or light. Here is a link to all of my posts on several books by Leslie Scalapino.

Suzanne Doppelt. Like the novelist Wright Morris, Suzanne Doppelt is one of those rare beings who is equally skilled at writing and making photographs. Since the early 1990s she has been exhibiting her photographs and publishing books that mix her poetry and her images. Her poetry often looks like a block of prose on the page, but it definitely reads like poetry and reflects her background in philosophy. Her photographs tend to appear in pairs or in grids of three or more, and the images rarely refer directly to anything in the text. This leaves the reader free to forge their own loose relationships of meaning—relationships between the images themselves and between the images and the text. Doppelt’s books might be said to share one central concern—perception in all its forms. I have written about her books The Field Is Lethal (Counterpath, 2011) and RING RANG WRONG (Burning Deck, 2006) here, but the book I now think is the best place to start is Lazie Suzie (Litmus, 2014), which the poet Eleni Sikelianos says is “a meditation on the senses, and in particular the enchanted lazy susan of the eye.”

Claudia Rankine. Claudia Rankine is quickly becoming a national treasure as she writes about America and racism. Three of her books (to date) include photographs, and you can start with any one of them. Don’t Let Me Be Lonely (St. Paul: Graywolf, 2004) is a powerful book about the struggle to find and maintain a moral position, to stave off loneliness and hopelessness, but to not fall prey to what Dr. Cornel West calls the blind and blinding “American optimism.” The most common visual trope in this photograph-filled book is an old-fashioned, mid-century family television set, into which Rankine has overlaid news media images or anonymous snapshots, suggesting the way in which we are confronted daily with a relentless tide of insults and tragedies and deaths that threatens to benumb us while we struggle with our own personal crises. I wrote more about the book here. Citizen: An American Lyric, (Minneapolis: Graywolf, 2014) uses photographs and other images to address the racism that is still so endemic in American life and that has permanently stained our history. And Just Us (Graywolf, 2020) focuses on whiteness and white privilege in America.

Eleni Sikelianos. Eleni Sikelianos has included photographs and other images in most of her books for the last twenty years or so. As is obvious from the example above, she can get very playful with the way she deals with the images in his poems. There are two terrific book choices to start with. The California Poem (Coffee House Press, 2004) is a book-length poem that attempts to give the reader an epic history of California from its glacial past to its rapaciously capitalist present. The book includes photographs, drawings, and a painting. Or try her more recent book Make Yourself Happy (Coffee House Press, 2017), which deals with science, mythology, history, ecology, extinction, and a host of other topics. I wrote more about that title here.

Ω

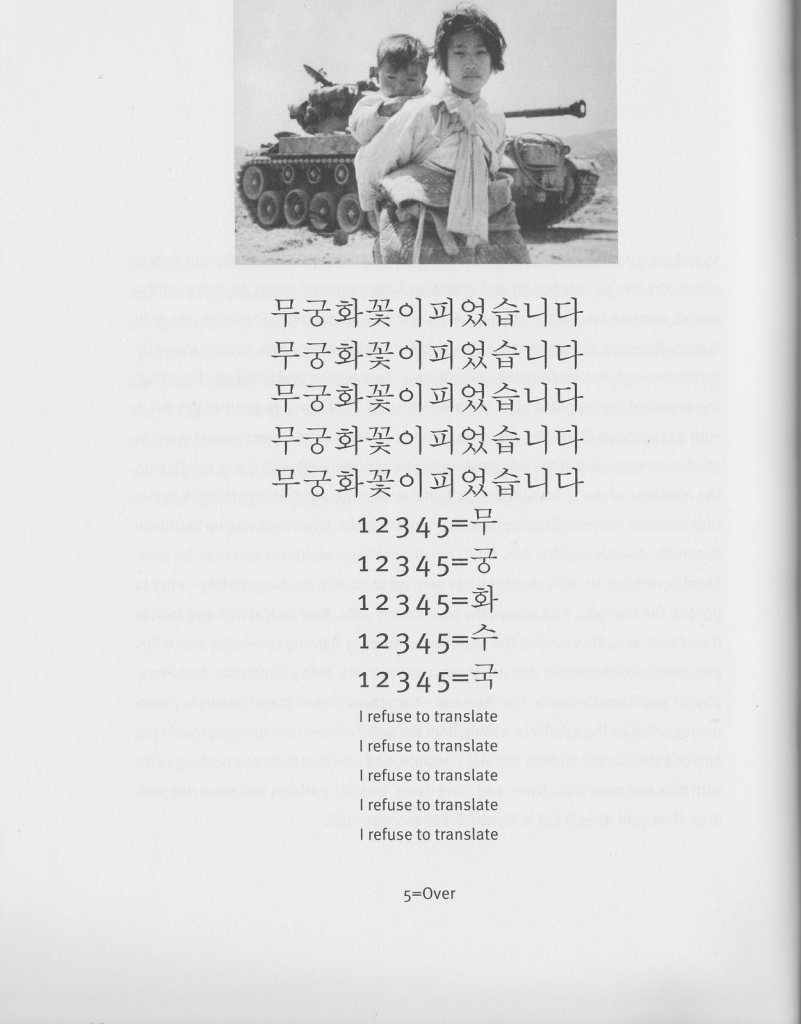

Don Mee Choi. Hardly War. (Wave Books, 2016). In Hardly War, Choi blends several languages, photographs, and drawings into a unified whole. She has a distinctive voice that is playful and confident, and Wave Books, as always, has produced a brilliant design that turns Hardly War into a bravura visual performance. Choi was born in South Korea and her father was a photographer and cinematographer who mostly worked in Asian war zones—including the Korean War and the Vietnam War. Choi deploys many photographs by her father in this book. She also borrows wordplay tactics from nursery rhymes and other forms of children’s poetry to give her writing a slightly sinister innocence, and she creates a strange and wonderful mashup of American and Korean cultures. See my longer post on this book here.

Anne Carson. Nox. (New Directions, 2010). Physically, Nox is a stunning accordion-fold book housed in a clamshell box. The poem Nox is comprised of dictionary entries, snapshots, scraps of paper, postage stamps, written memories, and other texts, all laid down across a scroll nearly 1,000 inches long on which we watch Carson cope with the death of her brother, as she tries to comprehend “the smell of nothing,” “the muteness,” and the meaning of memories scattered across a lifetime. Just as the physical book unfolds and then collapses back into itself, the unifying structure of Nox is the unfolding and collapsing of a short poem by the Roman poet Catullus. Nox opens with the poem—known as Poem 101—in Latin. As the scroll/book unfolds, Carson presents us with the individual dictionary entries for every Latin word in Catullus’ poem, along with her slowly evolving English translation of his poem. In parallel with the unfolding/translating of the Catullus poem, Carson examines the meager scraps that constitute her memories and communications with her brother, who lived his life largely abroad and estranged from his family. I wrote more about the book here.

Rachel Eliza Griffiths. Seeing the Body. NY: W.W. Norton, 2020. Griffiths’ powerful book deals with the death of her mother, the killing of a black man (Michael Brown) by police, her own rape, and other deeply personal topics. The book also contains a section of photographs entitled “daughter:lyric:landscape” that serves as a visual poem. We understand through implication that Griffiths is using these photographs to look back at herself through her deceased mother’s eyes. Like the novelist Wright Morris and the poet Suzanne Doppelt, Rachel Eliza Griffiths is an extremely talented photographer in addition to being a superb poet. She is known for her self-portraits. I wrote more about her book here.

Andrew Zawacki. Unsun:f/11 (Coach House Books, 2019). Many of the poems in Unsun draw on the terminology of scientific disciplines, not to mention a couple of foreign languages, as Zawacki tackles big subjects like the environment and technology. But mostly, he’s just walking in the fields and woods, thinking deeply. We often think of poetry as invoking mystery or pointing us to that which cannot be spoken, but Zawack’s writing aims at a kind of rigor or exactitude. There are still mysteries in this world, but in his hands they are all the more stunning if seen clearly. One section of Unsun is a series of poems and photographs called “Waterfall Plot,” which is an homage to the ‘Wheel-Rim River’ suite by eighth-century Chinese poet Wang Wei. Each of the twenty brief poems in this suite is paired with an abstract, black-and-white photograph by Zawacki. In these photographs, Zawacki makes the recognizable (an ordinary chicken coop) look otherworldly, turning it into ominous landscapes and skyscapes that serve as the inspiration for each of the poems. I have written more about the book here.

If it’s beginning to seem like using photographs is only for more experimental poets, consider John Updike. Updike, normally thought of as a novelist and short story writer, whose main subject, he once told a Life magazine interviewer, was the “American Protestant small-town middle class,” also wrote a considerable amount of poetry, including one significant poem sequence using photographs. In 1969, he used his own family photographs in a very innovative way in the title poem of his book Midpoint and other Poems (Knopf). “Midpoint” was written “to take inventory of his life at the end of his thirty-fifth year—a midpoint,” halfway toward his life expectancy of seventy. (He lived to be seventy-six.) I wrote more about the poem here.

Ω

You can explore my bibliography of nearly 1,000 title of works of fiction and poetry with embedded photographs by hovering over the pull-down menu at the top called Photo-Embedded Literature.